Agile development: How to prioritize a backlog, or How to assess business value in practice

A typical agile development story: a Product Owner (PO) gathers a list of user stories, the development team evaluates the cost of each story. But then comes another question: which feature to ship first? Unfortunately, there is no consensus yet on how to evaluate the benefit of a new piece of functionality. Let’s see the some of the techniques used to better assess the business value.

User Value

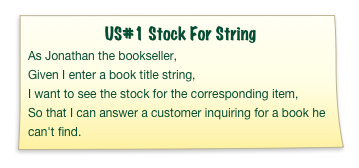

The title of a User Story should explain how the software can help a particular user achieve a particular task. This title should also clearly specify the user benefit. Take the following story for instance:

The value brought to the user (here, the bookseller) appears in the “So that…” part. In this example, the required feature helps to make a sell even though a book is not on the shelves. From a bookseller’s point of view, not going to the storeroom to check the available stock by hand is a huge progress.

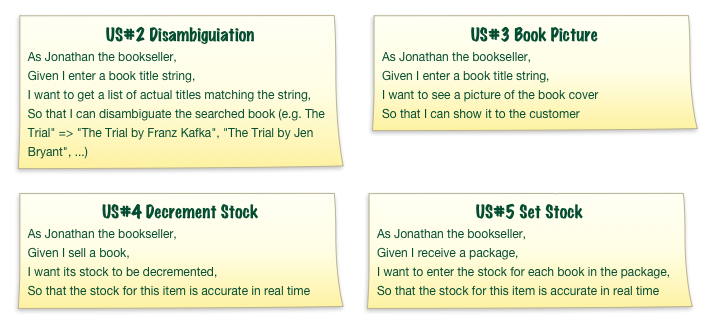

A PO may not be able to put a number on this story to quantify the benefit brought to the user. But it’s quite easy to see if the user benefit is higher than the one of other stories. For instance, could you compare the user value of User Story #1 with the value of the following stories?

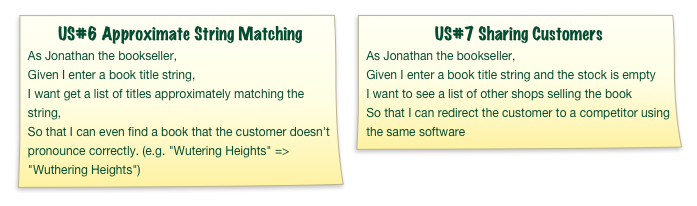

US#2 brings more value to the user than US#1, because without US#2, the software may display a stock for the wrong book, and cause a lost sell. US#4 and US#5 are required to let the software run. US#3 brings less value than other stories, because the software can work without it. That leads to a natural user value order (most important first):

This is how we usually evaluate user value in agile development: not using an absolute quotation, but by sorting stories. When the PO finds it difficult, classic techniques like tee-shirt sizing can help. To my mind, the best technique is to ask the PO to choose which stories should be in the product if it must be released the very next day.

You can find more details about writing user stories in this old post from 2008.

User Value is Relative to a User

By now, you have probably understood that the example product is a simple and generic stock management software provided as a SaaS solution for small businesses (bookshops, shoe stores, decoration stores, etc.). The product allows even non-experienced sellers to open a small, specialized brick-and-mortar shop, without spending too much on an ERP.

It’s important to know whose needs the product addresses. Sometimes it requires more knowledge of the end user to prioritize a story. Take the following stories for instance:

Does US#6 (approximate string matching) bring more or less value than US#3 (book cover picture)? And what about US#7? It’s hard to answer without knowing the bookseller’s business better. There is no universal way to sort these stories. It all depends on which types of customer the product targets. And that is a choice the PO must make early.

That’s why an agile project should always start by defining who the users are, and what their main goals are. So let’s go back in time, during the early days of the product definition.

Personas and User Needs

Even before writing the first user story, the agile product team had to work on a profile for typical product users. Such a profile looks like a short biography ; it explains the motivations guiding the user’s actions. It’s called a Persona. Here is an example Persona written for the stock management service:

Jonathan is an ex-gardener, who just loves gardening books. He has decided to create a brick and mortar bookshop to sell them. He knows that e-commerce competition is strong, but he is convinced that his own expertise in gardening can make the difference.

Jonathan often uses computers for his personal needs, but mostly for emails, Internet browsing and organizing pictures. Professional software like MS Excel intimidate him, and he’s always afraid to erase something by mistake. At age 42, he’s willing to use a new software for his business, but only if it doesn’t come with a user manual, and only if the outcome of his actions is foreseeable.

He is a lively and very social person.

During the same product definition phase, the product team listed the needs of each of the personas. They selected the needs to be addressed by the product, and left the other needs aside:

Jonathan needs to:

- Increase the time spent with customers

- Sell more books

- Increase the number of customers buying at least one book (avoid “showrooming”)

Reduce paperworkAutomate the book ordering processAutomate the accountancy

Based on these guidelines, the PO can determine that US#6 (approximate string matching) brings more value than US#3 (book cover picture). Getting answers for mispronounced titles will help customers to find a book they vaguely know. Showing the book cover on screen will only help the customers who have already seen the book somewhere else. Also, since Jonathan wants to differentiate his business from the e-commerce experience, he probably prefers to speak with customers face to face than to show them a computer screen. In a similar way, US#7 (sharing customers) doesn’t satisfy any of Jonathan’s needs, so it should definitely be far away in the backlog, if not completely removed.

So the PO can now reorder the product backlog, based on the user needs of the personas:

You can find more details about personas in the Persona page at Wikipedia.

Product Objectives

However, the stock management solution exposed here isn’t a gift made to Jonathan and other small business resellers. The primary objective of the product is to generate profit, based on a business model. The service brought to the user should justify a monthly subscription.

Let’s go back in time again, even further than the first time. Before the product definition phase, the agile product team worked on a list of product objectives. These objectives result from benchmarks of competitive products, user and marketing studies, simulated Profits & Loss, and the intuition of founders to create a sustainable business. What does the revenue depends on? What are the criteria for success? Continuing on the stock management service example, that could be:

Product objectives:

- Spend less than $5 per new visitor

- Transform at least 1% of visitors into paying customers

- Renew 95% of subscriptions each month

- Get 1,000 active customers by the end of the first year

- Enter the top 5 SaaS stock management solutions for small businesses within a year

Given these revenue-related objectives, does the backlog ordering change? Well, it seems that US#7 (sharing customers) gets a new light. It allows competitor booksellers to agree on using the same stock management software. Such collaboration feeds the mouth-to-ear engine of growth, increases customer retention, and reduces the customer acquisition cost.

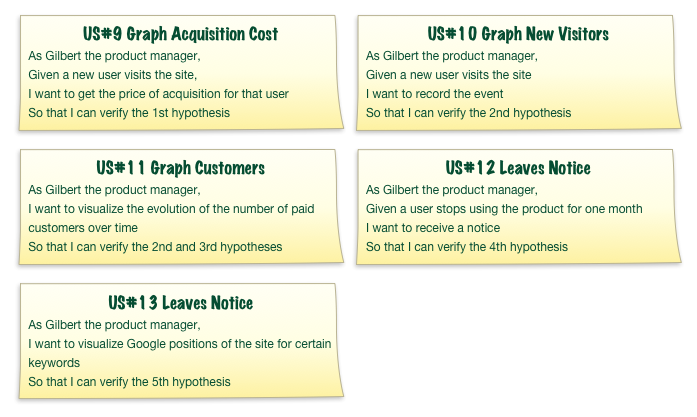

So based on product objectives, US#7 should be delivered before US#3 (book cover picture), and probably even before US#6 (approximate string matching). And it becomes clear that an additional user story has been forgotten, and needs to be implemented early:

Without this story, the product doesn’t have any chance to reach the first three objectives. But does it really need to be implemented first?

Validated Learning

Most digital products these days explore new areas in a universe of uncertainty. This universe has three dimensions: new technology, new usage, new business model. Finding an habitable planet in this universe is really hard. To put it differently, the objectives may bery well be impossible to reach. To acknowledge this uncertainty, the product objectives should be written as hypotheses:

Product hypotheses:

- The acquisition cost of a lead can be kept under $5

- The transformation rate can be kept above 1%

- The number of paying customers can grow by at least 50% every month

- The churn rate can be kept below 5% among paid customers

- The position of the service in search engine results can go up one page every month

Hypotheses and objectives cover the same items, but express them in a very different way. Hypotheses don’t start with an imperative verb, but with a metric definition. Hypotheses emphasize the possibility that something may go wrong.

Once the product owner has identified product hypotheses, the most urgent thing to do is to verify them. If one of the hypotheses proves wrong, then the product team must pivot. Otherwise, the product can’t reach sustainability.

That’s why in the early phases of the product lifecycle, most user stories are actually experiments. The goal of these experiments is to measure the metrics involved in each of the product hypotheses. Here is a list of experiments required to validate that the stock management service is sustainable:

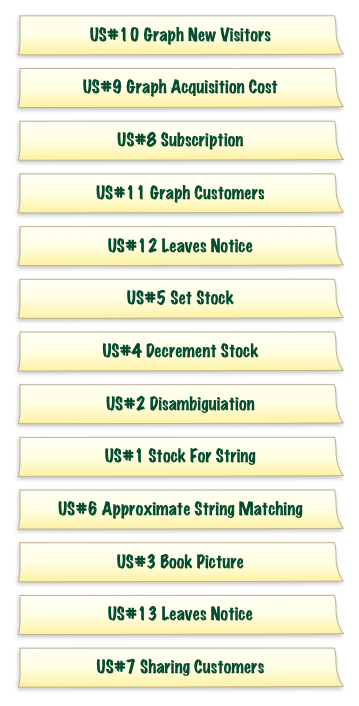

How important are these stories to the product? Very important: without them, the product runs, with no ability to drive it, or even to know if it goes in the right direction. Therefore, the ordered product backlog changes again, and ends up with:

Giving a high priority to the experiments allows the product manager to get usage facts, and validate the hypotheses supporting the business plan. This knowledge validated by experience, or “validated learning”, has a huge value for the product. Validated learning is actually one of the pillars of the Lean Startup (more information about validated learning).

It’s not only features

So the PO can leverage user value, revenue, and validated learning to prioritize features. Unfortunately, that’s not the whole story. A product backlog also contains bugs, technical work, and analysis tasks. How should these items be prioritized versus features?

Let’s start with the last item: analysis. Sometimes, during a planning poker, the dev team can’t evaluate the cost of a particular story. It’s usually because the devs need a better understanding of a certain piece of technology that they have never used before. Therefore, the product owner invests a few days of work to let the developers investigate further and acquire the proper knowledge. These tasks are obviously more important than the story they must help to quote. Besides, as explained in the previous section, acquiring knowledge has a huge value for a startup. So these tasks usually finish pretty high on the product backlog.

Refactoring, administration, technical consolidation and similar tasks are very hard to prioritize. Even if the technical team obviously understands how important technical tasks are, the product owner is often hard to convince. What is the business value of a day of refactoring that provides no additional feature? Zero, nada, zilch. Except if this refactoring allows the team to develop more features, faster, in the future. So the value lies in the future development cost savings ; it’s an investment. The main problem is that it is very hard to assess future savings. How much faster can the development team add new features once the refactoring is over? This requires good expertise, and most importantly, no stubbornness to pursue code quality for the sake of it. This is where the communication between the development team and the product owner must be honest and understanding.

And how about bugs? Bugs don’t have a positive value for the product, but a negative value as long as they are not fixed. Maybe the overall product value can be kept despite of bugs, by adding new (buggy) features. But this attitude does not stand on the long term. This is why many companies invest in smaller, but more polished, set of features. This boosts customer satisfaction. In the new economy, keeping a customer in the long term is at least as hard as getting new customers aboard. So bugs usually rate pretty high in the product backlogs.

This could all sum up to: don’t push features too much. A product regularly needs investment with no immediate user value to ensure stability, maintainability, security, and performance (i.e low running costs).

What is Business Value?

As much as possible, a story must express the way to assess its own value. Good stories contain the metrics required to validate their benefit. That means that the product team must spend time early in the product lifecycle to define the business value criteria.

There are many frameworks to assess the business value - some of them much more complicated than what I just illustrated. From my point of view, the business value of a user story can be assessed as a combination of user value, revenue, validated knowledge, and future return on investment. The stories to prioritize at the top of the product backlog are valuable on all these dimensions. Then, depending on the product maturity, the product owner may choose to push user value (to get more users), revenue (to increase the cash flow), validated learning (to better prepare the future), or stability (to boost customer retention).

Just like some developers think that a piece of code doesn’t really exist until it’s unit tested, many product developers think that a story doesn’t exist until its value has been proven. Except it’s not as easy as writing a unit test…

Tweet

Published on 12 Jul 2013